An extensive explanation about the Epsilon-Delta definition of limits

One of the most important topics in elementary calculus is the definition of limits. The definition says that the

if and only if, for all

, there exists a

such that if

, then

. In this article, we are going to discuss what this definition means. Readers of this article must have knowledge about elementary calculus and the concept of limits.

Review of Limit Basics

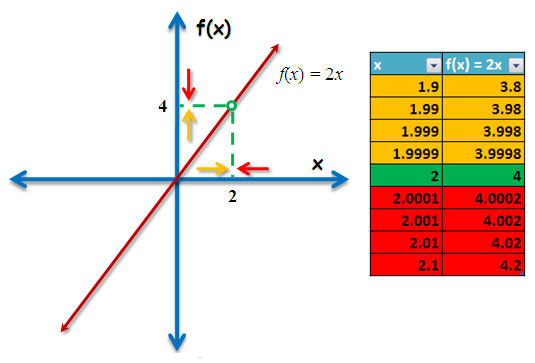

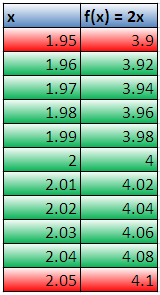

Consider the function . We have learned from elementary calculus that

. Aside from algebraic computation, this is evident from the color-coded graph and the table shown in Figure 1. The yellow arrows in the graph and the values in the yellow cells in the table indicate that as the value of

approaches

from the left of the x-axis, the value of

approaches

from below of the y-axis. On the other hand, the red arrows in the graph and the values in the red cells in the table indicate that as the value of

approaches

on from the right of the x-axis, the value of

approaches

from above of the y-axis.

Figure 1 – The table and the graph showing the value of f(x) as x approaches 2 from both sides.

From the above discussion, it is noteworthy to mention three things:

- We can get

as close to

as we please by choosing an

sufficiently close to

. For example, I can set

to

(with

nines) to get an

very close to

, which is

(

nines).

- No matter how small is the distance of

from

, a distance less than it may still be chosen. For example, if we choose the point which is very close to

, say a point with coordinate

with (

nines), we can still choose a value closer than this to

. For instance, we can choose

with

nines. This can be repeated for every chosen distance.

- Although

can be very very close to

, it does not necessarily mean that

equals

.

Now we go back to the definition of limits. In a specific example, the limit definition states that the if (and only if) for all distance (denoted by the Greek letter

) from

along the y-axis (directly above or below

) – no matter how small – we can always find a certain distance (denoted by

) from

along the x-axis (left or right of

) such that if

is between

and

, then

would lie between

and

.

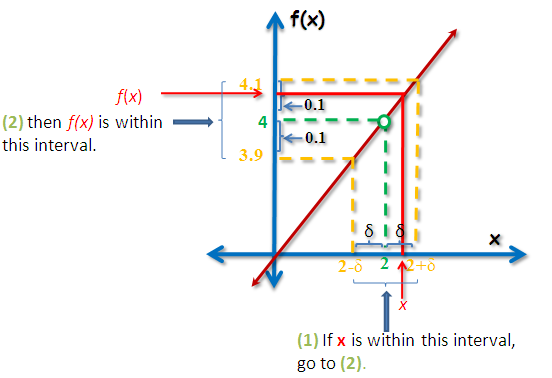

To give you a more concrete example, suppose we want the distance from

, which is our limit, to be

then the interval of our

is (

. The definition of limit says that given a distance

, we can find a distance

in the x-axis such that if

is between

and

, we are sure that

is between

and

. We do not know the value of

yet, but we will calculate it later.

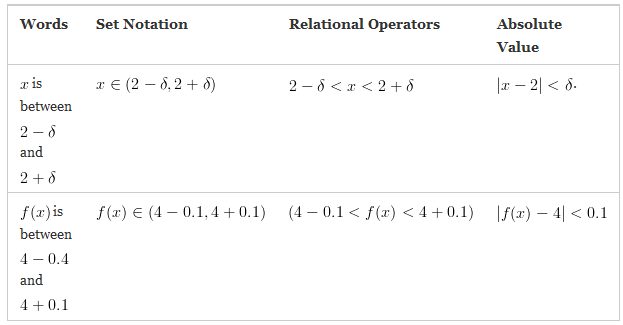

Figure 2 – The epsilon-delta definition given epsilon = 0.1.

In Figure 2, is between

and

or

. Subtracting

from all terms of the inequality, we have

. If you recall the definition of absolute value, this is precisely the same as

. The comparison among the notations is in Table 1.

Using the notations in the table, we can conclude that the following statements are equivalent:

- Words: Given

, we can find a

such that if

is between

, then

is between

and

.

- Set Notation: Given

, we can find a

such that if

, then

.

- Relational Operator: Given

, we can find a

such that if

, then

.

- Absolute Value: Given

, we can find a

such that if

, then

.

We have discussed that we can get as close to

as we please

by choosing an sufficiently close to

. This is equivalent to choosing an extremely small

, no matter how small, as long as

. Our next task is to find the

that corresponds to that

.

Applying this definition to our example, we can say the if and only if, given

(any small distance above and below 4), we can find a

(any distance from x to the left and right of

) such that if

, then

.

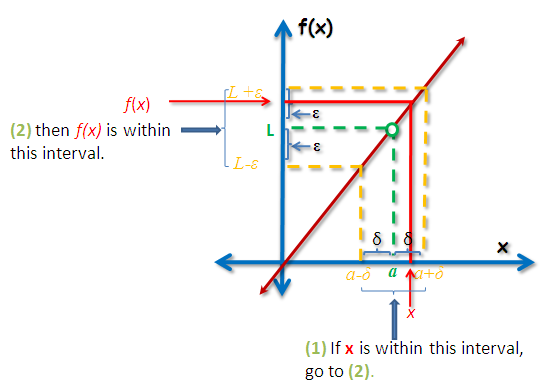

The Definition of a Limit of a Function

Now, notice that is the limit of the function as

approaches

. If we let the limit of a function be equal to

and

be the fixed value that

approaches, then we can say that

if and only if, for any

(any small distance above and below

), we can find a

(any small distance from to the left and to the right of a) such that if

then,

. And that is precisely, the definition of limits that we have stated in the first paragraph of this article.

Figure 3 – The epsilon-delta definition given any epsilon.

In mathematics, the phrase “for any” is the same as “for all” and is denoted by the symbol . In addition, the phrase “we can find” is also the same as “there exists” and is denoted by the symbol

. So, rephrasing the definition above, we have

if and only if,

, such that if

then,

. A much shorter version of this definition is the phrase

, such that

. The symbol

stands for if and only if and the symbol

is similiar to if-then. If

and

are statements, the statement

is the same as the statement of the form “If

then

“.

Finding a specific delta

We said that given any positive , we can find a specific

, no matter how small our

is. So let us try our first specific value

.

From the definition, we have if and only if, given

(any small distance above and below 4),

such that if

then,

.

Now . This implies that

which implies that

. Simplifying, we have

. This means that our

should be between

and

to be sure that our

is between

and

. This is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – The table showing some of the values of epsilon and delta satisfying the definition of limit of 2x as x approaches 2.

Now, let . This means that our interval is

. Now

. Thus,

which implies that

. Solving, we have

. This means that our

should be between

and

to be sure that our

is between

and

. There are only two examples above, but the definition tells us that we can choose any

so let us generalize our statement by doing so.

Now . This results to

which implies that

. Solving, we have

. From the condition above,

so we can let

.

This means given any , we just let our

equal to

and we are sure that if

is between

and

to be sure that our

is between

and

.

In the next calculus post, we are going to discuss the strategies on how to get given an arbitrary

value, so keep posted.

Related Articles

- Understanding epsilon-delta proofs

- An Intituive Introduction to Limits

- Counting the Infinite: A Glimpse at Infinite Sets

- Epsilon-delta proof: example 1