We have learned from elementary school mathematics that a prime number has only two factors, 1 and itself. For example, 2, 3, 5 and 7 are prime numbers, while 8 is not prime because it has four factors — 1, 2, 4, and 8. Numbers that are not prime are called composite numbers.

Geometric Interpretation of Prime and Composite Numbers

Mathematicians during the ancient times, particularly the Greeks, always make use of geometric interpretations of numbers. Square numbers, for example, are represented with pebbles arranged with the same number of rows and columns. The first five square numbers are 1, 4, 9, 16 and 25.

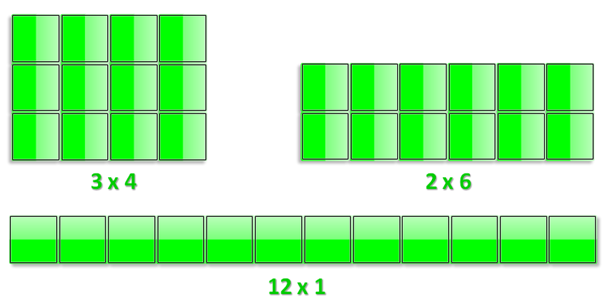

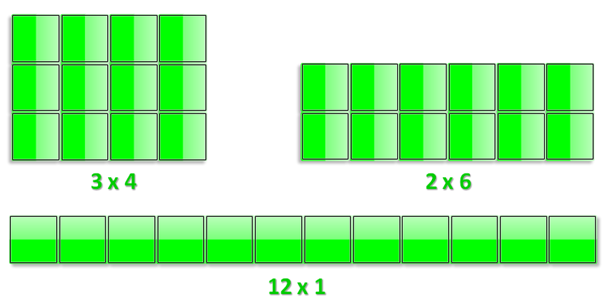

Rectangular numbers are also popular. For instance, the number 12 can be interpreted pebbles arranged in rectangles with the following dimensions: 3 by 4, 2 by 6 and 12 by 1. If we are going to use squares instead of pebbles, the geometric representations of these arrangements are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Different rectangular arrangements of 12 pebbles represented by squares.

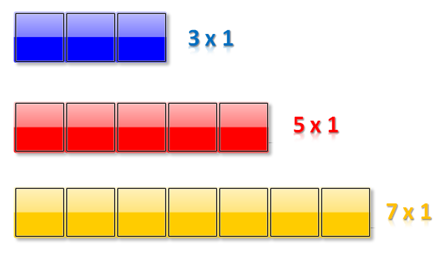

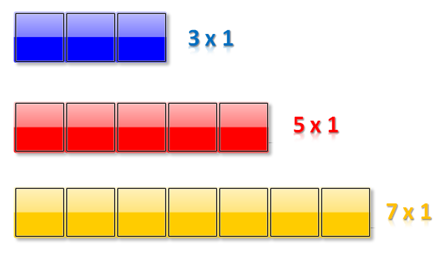

Numbers that cannot be arranged as more than one rectangle are prime numbers. In our example above, 12 has three possible arrangements, while the numbers 3, 5 and 7 can only be arranged in a single row.

Figure 2 – Rectangular arrangements of 3, 5 and 7 pebbles represented by squares.

As we can see, this is the geometric interpretation of the definition that the factors of primes are only 1 and itself.

Sieve of Eratosthenes

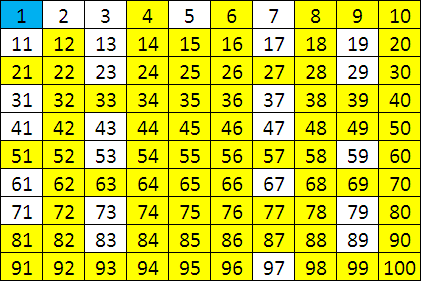

The Greek philosopher and mathematician Eratosthenes was the first to be credited in identifying primes in a finite list by brute force. The strategy is to list a finite set of counting numbers in increasing order, then starting with 2 eliminate all its multiples. This eliminates all even numbers except 2. Then we follow the same pattern: we eliminate multiples of 3 greater than 3, eliminate all multiples of 5 greater than 5 and so on, until all the numbers left are not multiples of any number smaller than it. The remaining numbers after all elimination are prime numbers.

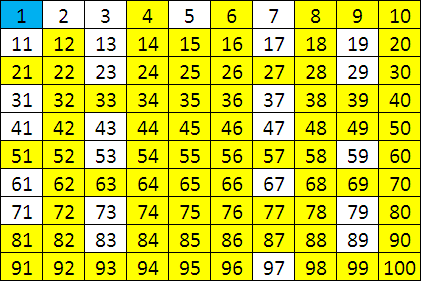

The primes numbers less than 100 are shown in white cells in the table below. The numbers in the yellow cells are composite numbers. Mathematicians agreed not to include 1 in the set of prime numbers or the set of composite numbers.

Figure 3 - The sieve of Eratosthenes shows primes less than 100 in white table cells..

If we look at the table above, we could not probably see a pattern about the number of primes in a given interval; however, if we investigate further, as the intervals increase, the number of primes is getting fewer and fewer. For example, there are 168 primes between 1 and 1000, 135 primes between 1000 and 2000, 127 primes between 2000 and 3000, and 120 primes between 3000 and 4000. With this observation, we want to ask the following question:

Is there a particular prime number, that after such number, we could no longer find primes?

or equivalently,

Are prime numbers finite?

We will answer this in the continuation of this article titled “Infinitude of Primes.” The formal proof of this conjecture is also discussed in the third part.